The conversation around trauma

Trauma talk is on the rise. Are we ready for everything it might mean?

The other day, I saw someone speculating on social media about how to reach a person who was interacting in some difficult ways. A commenter suggested looking into the possibility of trauma, “simply because it’s so common.” The comment, made casually, underlined what I consider a tragedy of the modern age. Which is to say: we are living in a traumatized—and traumatizing—era, and nearly everyone is affected.

The classic line “Hurt people hurt people” may be glib, but unfortunately it describes the world we’re living in, where individual trauma collides with intergenerational trauma in the context of broader societal trauma, and the social structures that might help are largely absent or inaccessible. But the growing awareness of these deep-seated issues means that at least some change is happening.

Talking about trauma

I notice that the cultural conversation around trauma is much more alive these days than it was even five years ago, certainly than ten years ago, when I graduated from my training program. Back then, I was talking about a lot of interesting stuff in my blog, but I wasn’t talking about trauma that much. We talked about it in the training; we dealt with a lot of it in the training for sure! But back then, I was near-constantly surprised at how many people around me had deep and not very processed trauma—and I had very little sense of my own. As you might imagine, this combination of factors led to a lot of painful and at times ugly collisions at the intersections of all our Stuff, as folks sometimes call it.

But now, everyone seems to be talking about their Stuff. It’s all over our media, it’s in the plots of cartoons, it’s deep in discussions of social justice, it’s a concept that is reshaping the way people in helping professions think about that help. But I recognize that just because I see it everywhere doesn’t mean that everyone knows what I’m talking about when I say “C-PTSD” or “dysregulation” or “dissociative habits.”

I want to talk about all of that Stuff here in Write It Out, and so I thought it’d be a good idea to start by defining some terms—or at least to talk a bit about my understanding of them, and how it’s developed. For this week, I want to talk about the T-word itself: its breadth, how it affects people long after the fact, and the changing conversation about care.

What do we mean by trauma?

A lot of times, when people talk about “trauma,” they’re really talking about the long-term impacts of trauma. The word trauma itself simply means a major injury of some kind. In medicine, it can refer to a physical injury, like a head trauma, or injuries from a car accident. It can be a mental or emotional injury, such as a rough breakup, the sudden death of a loved one, a natural disaster, or a parental divorce. Often, the ones that have long-term effects are both physical and emotional: experiences of war, sexual assaults, abusive relationships, survival of violent crime, childhood abuse and neglect, and medical traumas.

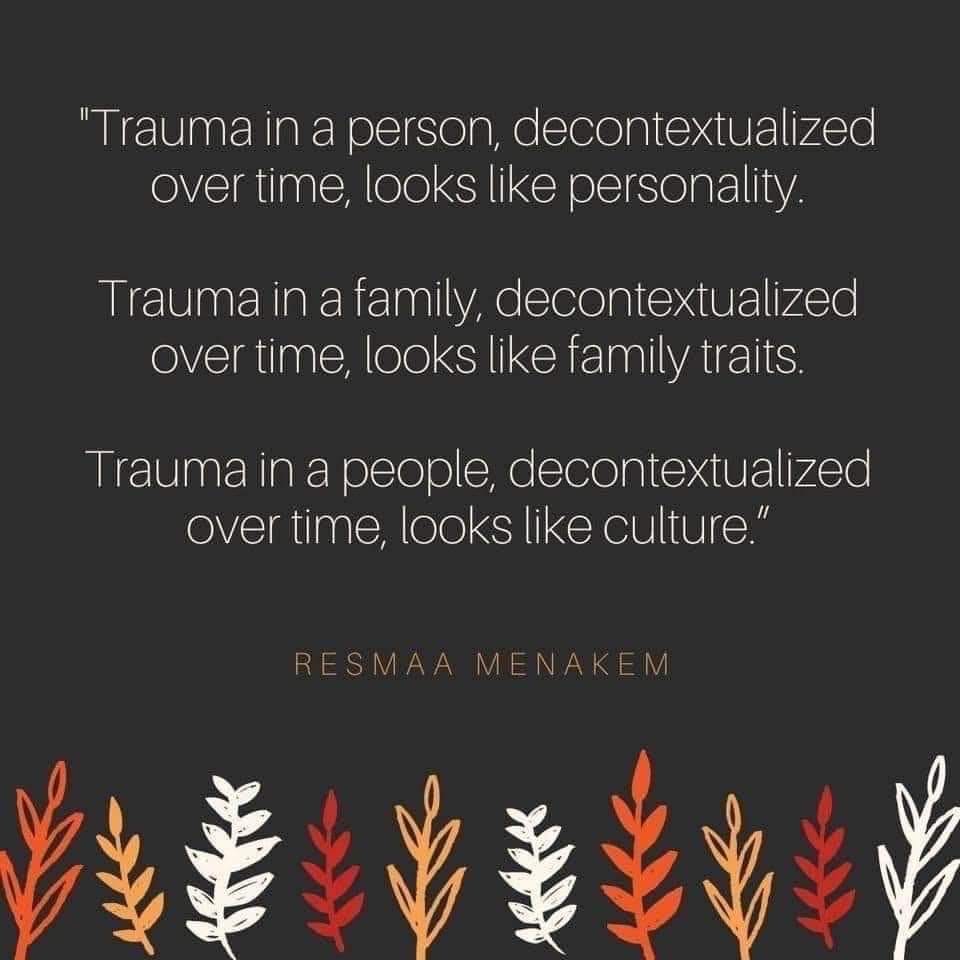

But while many traumas happen to individuals, a great many of those exist in the context of intergenerational trauma. That is to say, for example: a person who hits their kids or is violent in their intimate relationships likely experienced violence in their upbringing—from people who probably grew up under similar circumstances. Familial trauma is a cycle that is difficult to break. More recent research in the field of epigenetics even indicates that things that happened to grandparents can be encoded in the body, such that the descendants of Holocaust survivors become more susceptible to PTSD, anxiety disorders, and metabolic issues. Trauma almost always happens in context.

Opening out still further, there are even broader traumas that occur on the societal level. These include systemic issues like poverty, racism, colonialism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, environmental racism, and many other factors that affect large groups of people on a daily, ongoing basis, such that the regular experience of living constitutes an ongoing trauma.

I have also argued (and I’m certainly not the first to do so) that America in late-stage capitalism is a traumatic culture, and that day to day, people on all levels who are operating within it are experiencing a structure that crushes the health and vibrancy of their bodies and spirits. The rhythms of the nervous system—our needs for rest, play, connection, and safety—are regularly disrupted by the relentless demands of the workplace, the onslaught of media influence, the isolation of the nuclear family, the lack of community support for childcare, the neglect of our elders and disabled folk, the commodification of self-care, the pressure of conformity, the devaluing of rest and idleness, the overvaluing of money and success, and the connection of body- and mind-breaking labor to basic survival.

So what do we do about it? Not nearly enough, it turns out

All of these traumas (large and small, individual and collective) interact complexly with the human experience, but some people escape the more severe long-term effects of it. But when trauma has lingering impacts on daily life, socialization, and behavior, that’s when we start talking about trauma-related “disorders,” the most well-known of which is PTSD.

I put disorders in quotation marks not because I have an inherent distrust of the way our mental health care system quantifies mental health using diagnoses, although to be fair I kind of do. But more to the point, there is a tacit understanding that if your mental health challenge or disability doesn’t prevent you from working (i.e., from being a “productive” member of society), then it somehow doesn’t “count.” The usual diagnostic threshold for distress to tip over into being named a “disorder” is that it seriously disrupts your life: that is to say, it keeps you from sleeping, or eating well, or of course, from working.

For those who are clearly traumatically adapted but don’t qualify for diagnosis—which is to say, those of us who struggle with the expectations of daily living in modern society, but somehow keep miserably muddling along—we might be able to get help, but our struggles are framed as problems to be fixed rather than highly understandable bodily responses to a world that is badly broken. The “cure,” as it were, is the ability to return to the demands of modern life, which for many of us, is also the cause of the disease.

The most horribly sublime irony of this is that those who need the most help are least likely to be able to access it under the diagnostic model, whether financially due to expensive care and/or lack of insurance, or practically due to the process of finding a therapist being so convoluted. It’s hard to pay for therapy if you can’t work. (Often even if you can.) It’s hard to find a therapist if you’re having trouble with everyday tasks.

There’s also the problem, raised by anti-racist thinkers, of therapy itself being a very white-centered and decontextualized solution to a problem that disproportionately affects the most marginalized populations. Paying a therapist (yes, even me) $100 or more per hour to meet once a week outside one’s usual context can be and often is helpful. But this expensive and siloed approach highlights the fact that support for people’s struggles is vanishing, or has vanished, within the structures that are meant to sustain us: parents, intimates, extended families, friend groups, communities, even workplaces. In fact, where those structures do exist, they are also often exacerbators of trauma, due to the multilayered impacts of a culture built around profit rather than care.

So how do we begin to approach these deeply intertwined problems? The more I go into it, the more it seems like a total restructuring of society is necessary. For now, I can only approach it with the powers I myself, also a trauma survivor, have at my disposal. But a broader conversation is at least beginning, and I mean to be a part of it.

In an upcoming newsletter, I’ll be talking more about PTSD, C-PTSD, attachment styles and disorders (there's that word again), and more about untangling one’s own traumatic patterns. For now, I hope you’ll take this post as an invitation to continue this conversation and comment with your thoughts.