On this dreadful day in history, I’m here to bring you the distraction provided by a long and angry review of Nosferatu (2024). I hope you enjoy it. Spoiler alert, obviously, for the entire film.

**

It’s rare that a film makes me truly angry. I can be moved or unmoved, I can be disappointed when a film doesn’t reach its potential. Once in a while though, a movie really just irks the crap out of me.

Usually, the fault is ideological. I’ll never forget standing up and screaming “what the fuck?!” in the theatre at the end of 300, then being unable to get any man in my life to take seriously my complaints that the movie was homophobic, racist, bloodthirsty fascist propaganda for the Bush wars. (I was right of course, but what of that? It was no more fashionable for a woman to be heeded then than it is now.)

Sometimes, though, and in these troubled times, it is more intense frustration at the howling emptiness at the center of the spectacle. The meaningless of it all, and at such expense. What a colossal fucking waste, is the point. Couldn’t that $50 million have gone to, I don’t know, literally anything else?

No, apparently it had to be another remake of Dracula

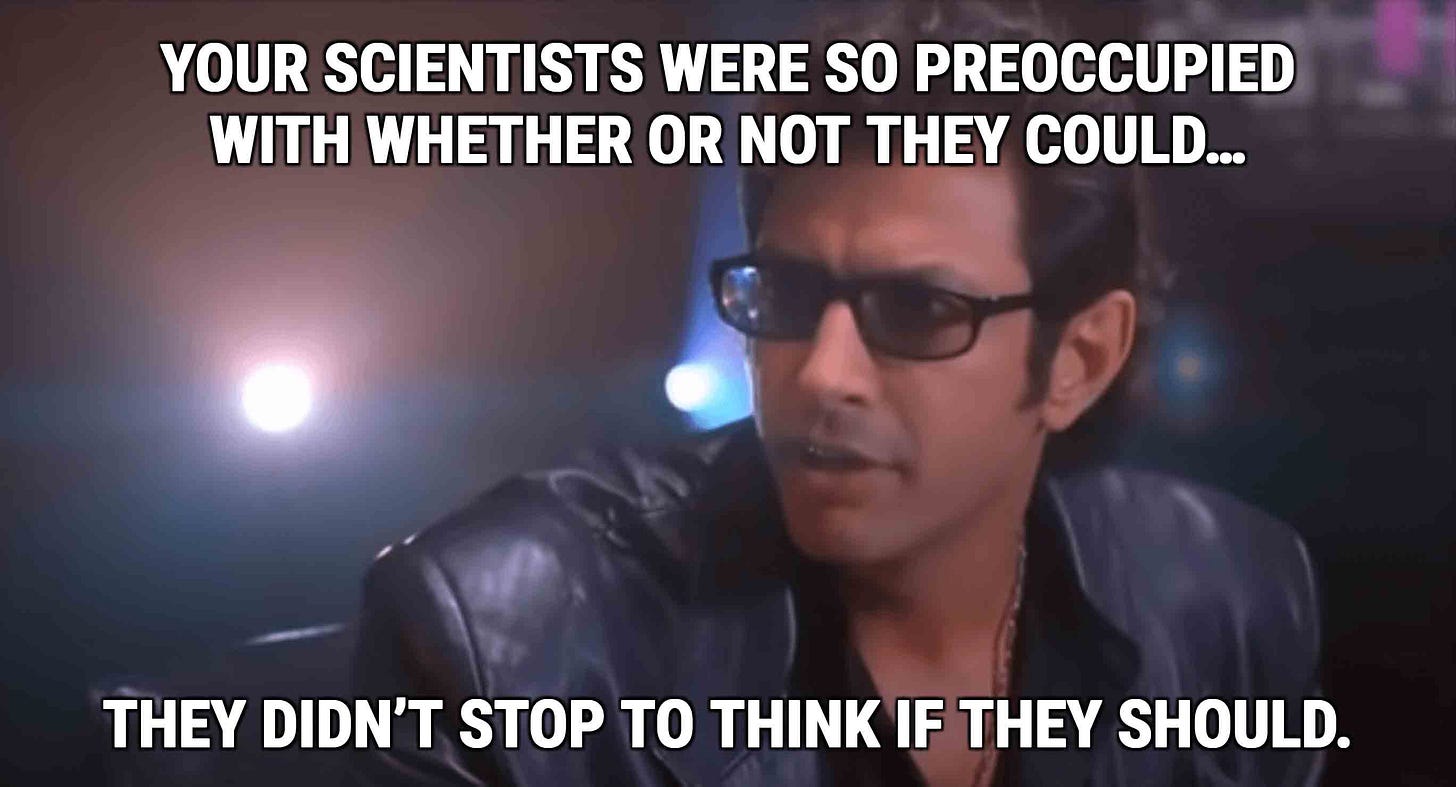

There’s a powerful something-or-other at play these days in Hollywood. I mean spoiler: it’s capitalism, obvi. But while capitalism has always been the enlarged, plaque-encrusted heart of Hollywood, there’s a more sinister bent to it in the past few years. Too many movies are getting remade that are already deathless classics, and too many of those are subject to what I’d call the Jurassic Park fallacy of moviemaking.

I mean, I get it. Bram Stoker’s Dracula and the gothic-era horror-romance in general are deeply compelling narratives, demanding to be told over and over again. There’s a reason there are a thousand and one vampire stories, werewolf stories, monster stories, creature stories. Hell, I thought Penny Dreadful was one of the coolest and most touching shows I’d ever seen.

But Penny Dreadful took these old figures and transfigured them, gave them new life and emotional depth, mashed them together into a singular, claustrophobic world, dialed up the pathos and suspense and tragedy until it was nearly unbearable.

And it had Eva Green. (I am only human after all, though I’m not sure she is.)

What I cannot for the life of me figure out is what compels a filmmaker, who by all accounts is brilliant and has done wonderfully outré and original horrormaking in the past, to attempt to recreate a German Expressionist masterpiece that was already beautifully re-realized once. Is there some law that Nosferatu must be remade every fifty years or something?

Good EVEning

An answer might start with the question: what is it that makes the Dracula story so sticky? (Besides all the blood I mean.) Vampire stories are one thing, and those stories are much older than Stoker, and continue because of the richness of symbology vampires offer us. Cannibalistic urges, monstrosity, sin versus purity, temptation and the obvious sexual metaphor, the idea of redemption, a human turning from the good but perhaps back toward it, the beauty and the beast narrative. Vampires have been done to death (ha) because they’re such a rich vein (haha) of story. I love ‘em, and I don’t think they’ve been worn out.

But the Dracula story in particular is in many ways a bit sluggish these days, its themes a bit stodgy, not to mention confused and low-key racist. What still has teeth (okay stop it already), I think, is not the characters (was there ever a more boring character than Jonathan Harker??) nor the plot (doesn’t make a ton of sense), but the Gothic horror itself. Notice that however many times someone does Dracula with the characters and themes drawn from that book, they always focus on recreating the atmosphere, the mood, something of the period. Nobody sticks the Count in a penthouse in L.A. (Or perhaps they do, but nobody remembers it, or it’s meant to be comic.) We want the dark ruined castles. We want the Carpathian Alps. We want Mina Harker in a white full-length nightgown, fainting in fright. We want Dracula to open a slow, creaking door to us and cast his eyes over us hungrily. Dracula is like 87% vibes.

Whereas this Nosferatu is basically 100% vibes

I’m a fan of the original 1922 silent Nosferatu, but even more of the spellbinding 1979 remake by Werner Herzog. In the original, German Expressionist filmmaker F.W. Murnau ripped off the majority of Bram Stoker’s story, changed all the character names, flipped a few story details, and created a silent masterpiece that appealed to German audiences (though it didn’t so much evade copyright laws; turns out Stoker’s widow sued and we almost lost all copies of the film afterward).

Unlike in later adaptations, starting with the elegant Bela Lugosi Dracula of 1931, Nosferatu’s Count Orlok was monstrous, spectral, bald and pointy-eared, more like a human-bat hybrid than a seductive dark prince. The famous shots of his clawed shadow on the steps, his body rising straight to a standing position with no apparent effort from his coffin, and other stark, dramatic images cement the work as a paragon of the style of this era.

Silent movies in general can be seen today as “overacted.” The actors of the time were used to playing on stage, where broader movements and facial expressions were called for. But the movies were also silent, which means that so much more needed to be communicated through movement and expression. German Expressionism was also so deliberately artificial, symbol-rich, and painterly that the films of Murnau and Fritz Lang are closer to the earlier name for these things — “moving pictures” — than nearly anything that came afterward. They are that much further removed from reality that they have the quality of dreams.

Perhaps that is why Herzog’s version, made more than fifty years later, captures so much of the same dream-like horror, even as it makes itself utterly its own. Herzog made the film in German (though there is a separately shot English version), hired the terrifying Klaus Kinski to play the vampire, and while he set it in period, he also added a more modern sensibility to Dracula’s plight. This Count is dangerous, yes, bloodthirsty, amoral. But above all he is tired, and so, so bored. In the late ‘70s, the German idea of the eternal vampire is one of profound ennui.

Stylistically, while Herzog nodded to some of the German Expressionist ideas — the luminous Isabelle Adjani pulls some real silent-film faces and reactions, for example — he widened his lens, shining light on everything, taking in the sweep of the countryside, and making the day as foreboding as the night. Divided Germany, in 1979, is seen through the horror of the mundane, and the surreality of a world that has ceased to make sense.

Not-feratu

I may be in danger of undermining my own argument here, since what I’m essentially saying is: Herzog remade Nosferatu with the aim of honoring its silent and Expressionist ancestry, while making it appeal to contemporary sensibilities and executing his own vision. I can hardly argue the Robert Eggers did any differently in his own new adaptation. His visual world is gorgeous, dark and full of ruined castles and claustrophobic city streets in the rain. He recreates the shadowplay of Orlok’s clawlike hand. He tells the same story, with some new twists. And he leans hard into horror tropes he knows his contemporary audience will want: blood, rot, decay, writhing and moaning that might be suffering or might be lustful (probably both), monsterfucking.

Where it all falls down for me is the lack of emotional depth, the muddied themes, the intense reliance on gross-outs and dark erotica, and worst of all, the ceaseless recitation of exposition. For a horror movie — and horror movies used to upset me so much as a child that I couldn’t watch them at all! — this didn’t grab me, didn’t move me, didn’t fill me with dread or vertigo or chills. My primary experience during much of the film was boredom. At the end, I commented, “I never thought a movie with so much blood in it could be so bloodless.”

This movie sets itself up as a clockwork recitation of its tale. It sets its stage and drowns it in melancholy; it asks its actors to behave in wooden ways, reminiscent of silent actors; its sound design is aggressive, alternating between ominous silence and too-close breathing, slurping, whisper-growling in various languages, etc. It seeks, in essence, to grab the audience by the throat from the word go, while having characters literally grabbed by the throat as often as possible.

But the storytelling see-saws between saying nothing at all about what’s happening and saying far too much. From the start, I felt as if I was being shown scene after scene of something akin to fanservice: the smug, “Ah yes, remember this story beat? How about this plot point? Bet you’ve never seen this part of the story put quite like this!” It felt too reliant on the audience’s foreknowledge of the story.

Yet at other points, the characters are at pains (mostly mine) to explain the details of the journey they are on in detail. Discourses abound, on Ellen’s “melancholy,” on the friend-couple characters’ insatiable desire for each other, on the ruined Count’s inability to love, on how terribly much Ellen loves Thomas while also being inextricably linked to an ancient evil for reasons that are never given. None of it reads, none of it shines through the performances. They’re all just yelling their feelings aloud.

The sexuality, too, is a muddle. I think we’re meant to understand that Mina/Ellen’s “free will” in offering herself to Orlok as a sacrifice makes her…empowered? Or something? But like this is a guy she’s been in thrall to for literally her entire adult life? So what does her consent even mean at this point — also coerced as it is by Willem Dafoe’s character? As for the climactic scene…sigh. It’s too graphic to get into here, but let’s just say that she seems to enjoy their “union,” and he’s so distracted by the goal he’s been chasing the entire film that he…dies at sunrise, something he’s managed to avoid for centuries. (Oops!) And then, having done her sacred duty or whatever, she dies. (Great.)

The result, for me, is that none of the emotional weight, stakes, or gravitas the movie severely looks like it should have actually came across to me. I felt like I was being shown a lavish picture-book, with trite, empty pronouncements written alongside each frame.

There’s a reason silent films are silent

I’m reminded of a show I did just before leaving the Boston area. It was an adaptation of the silent film Metropolis, as a radio play. It was a radical idea: rather than having the audience rely near-exclusively on visuals, adapt so that they rely near-exclusively on audio.

It was okay, and I appreciated being part of such an ambitious project. The trouble was, the story behind Metropolis is unforgivably stupid. The film endures because of its stunning visuals, all the intense things that nobody had ever achieved on film before, and the dancerly performances. But translate it back to words and it loses a lot of its magic. It becomes a trite recitation of an old story that doesn’t really resonate anymore. Absent the magnificent visual ballet of it all, it kind of falls flat.

To me, this new Nosferatu feels like Eggers tried to have it all: the lush visuals, a silent-film style, a more liberated sexuality, modern horror gross-outs, plus allllll the words. Put it all together and it’s kind of a mess. I would have liked this version of what Murnau called “A Symphony of Horror” much more if each character were permitted more than one note, if they interacted with each other in ways that made emotional sense, if there weren’t so much over-explaining in parts that didn’t need it and under-explaining in parts that did.

Herzog did a thing in his version that still makes me stop breathing when I watch it. Take a look at this. Two and a half minutes. The characters say four lines. The camera tracks the two of them across the long room without breaking away once. There’s no music. Just the predator and the prey sharing a tensely intimate dinner. It’s goddamn mesmerizing.

Some of this new Nosferatu is quiet. But none of it has the pace, the drawn-out tension, the patience that Herzog’s has. I wasn’t drawn in, couldn’t be, because nobody was doing any drawing. Only striking, grabbing, writhing, screaming, and if I wasn’t willing to come along, then I was going to get left behind.

This might be what made the whole thing fall apart for me, ultimately, at the same time as many others seem to have adored this movie. I didn’t go into it skeptical, refusing to be grabbed. Nonetheless, I was not taken in, and especially after the opening scene, I didn’t feel like any further invitations were forthcoming. For others, they showed up pumped, let Eggers do his thing, and were fully invested.

I don’t think this movie was bad, per se. If it were just bad, I would never have spent all this time and energy writing about it, thinking about it. I just think it was trying to do a whole lot of things at once, and not fully succeeding at any of them. The impression I was left with was one of empty spectacle — and very expensive empty spectacle at that. $50 million an awful lot of money for a film with a lot of gorgeous and grotesque imagery, but no stakes (haha), suspense, emotional weight, character development, or moral center. (Which is to say: I still have no living idea what the hell Eggers is trying to say.)

But other than that, Mrs. Lincoln

So why did this make me more upset than, say, whatever the latest Marvel monstrosity was? Talk about extremely expensive empty spectacle: Marvel Studios could have solved world hunger probably a hundred times over by now. How much did fuckin’ Age of Ultron cost? (Okay I guess I’m a little mad about it.)

I guess it’s because I expected better. I fully expect the Marvel juggernaut and its competitors to churn out tripe year after year and for the audiences to keep eating it up and saying it’s filet mignon. Once in a while we get Black Panther or Thor Ragnarok or Loki, and while that doesn’t make it all worth it I guess I’ve inured myself to the idea that there always is and always will be huge, bloated, overproduced schlock and that it is the backbone of the “entertainment industry,” and from time to time a fingernail clipping from that massive body will fall and be allowed to become The Princess Bride or whatever other perfect movie I can think of that was clearly made from the heart and with enormous care.

This one felt like it was made with enormous care, is the thing. It feels like something Eggers cared about a great deal. (I still haven’t gotten around to watching The VVitch, vvhich I understand is amazing.) It doesn’t seem like the kind of movie that’s just about making its money back. It seems like it’s trying, very hard, to say something important.

It’s just massively unclear what. Possibly because it’s being drowned out by Orlok’s intensely wet breathing.