How is this supposed to work?

Or, what is therapy for, anyway?

When clients look me up for therapy, I often find that they’re specifically looking for someone like me. To be clear (and as I’ll likely repeat with some frequency), I’m not a state-licensed social worker or mental health counselor or psychologist; I’m a certified Somatic Therapist who has completed a four-year training, plus ten years of experience and continuing education (and self-education). As such, “someone like me” is a therapist or healer within the wide-ranging and admittedly sometimes suspect world of “wellness.”

Sometimes, clients who come to see me are seasoned veterans of therapy, and are looking for someone who operates outside of the mental health care system. Other times, folks have never been to therapy before, and aren’t even sure how it’s supposed to work, but like what they see in my profile or on my website. Many of my clients are people with marginalized sexual or gender identities or relationship modalities, and are seeking someone they won’t have to educate before they can get help.

I don’t work outside of the mental health care system out of any particular animosity toward that system, though I have seen the way it can chew through therapists, and subsequently, how burned-out therapists can sometimes chew through clients. I do see such clients from time to time: people who’ve had bad experiences with traditional therapists and want something different.

What does it mean, then, when potential clients seek my help, rather than that of a more traditional therapist? Often the answer to that, I think, comes from the question in today’s subtitle: what is therapy actually for? How do therapists—even non-traditional ones—actually help their clients?

I’ll insert the usual wisdom here about how every client is different, and how much of the help that can occur happens due to the connection and relationship between an individual client and an individual therapist who are well-matched. But I do believe there are a few key things that any kind of therapist ought to be offering their clients, and it’s frankly shocking to me when they don’t. The following elements of a successful therapeutic relationship may sound pretty obvious, but you’d be surprised how often they’re missing.

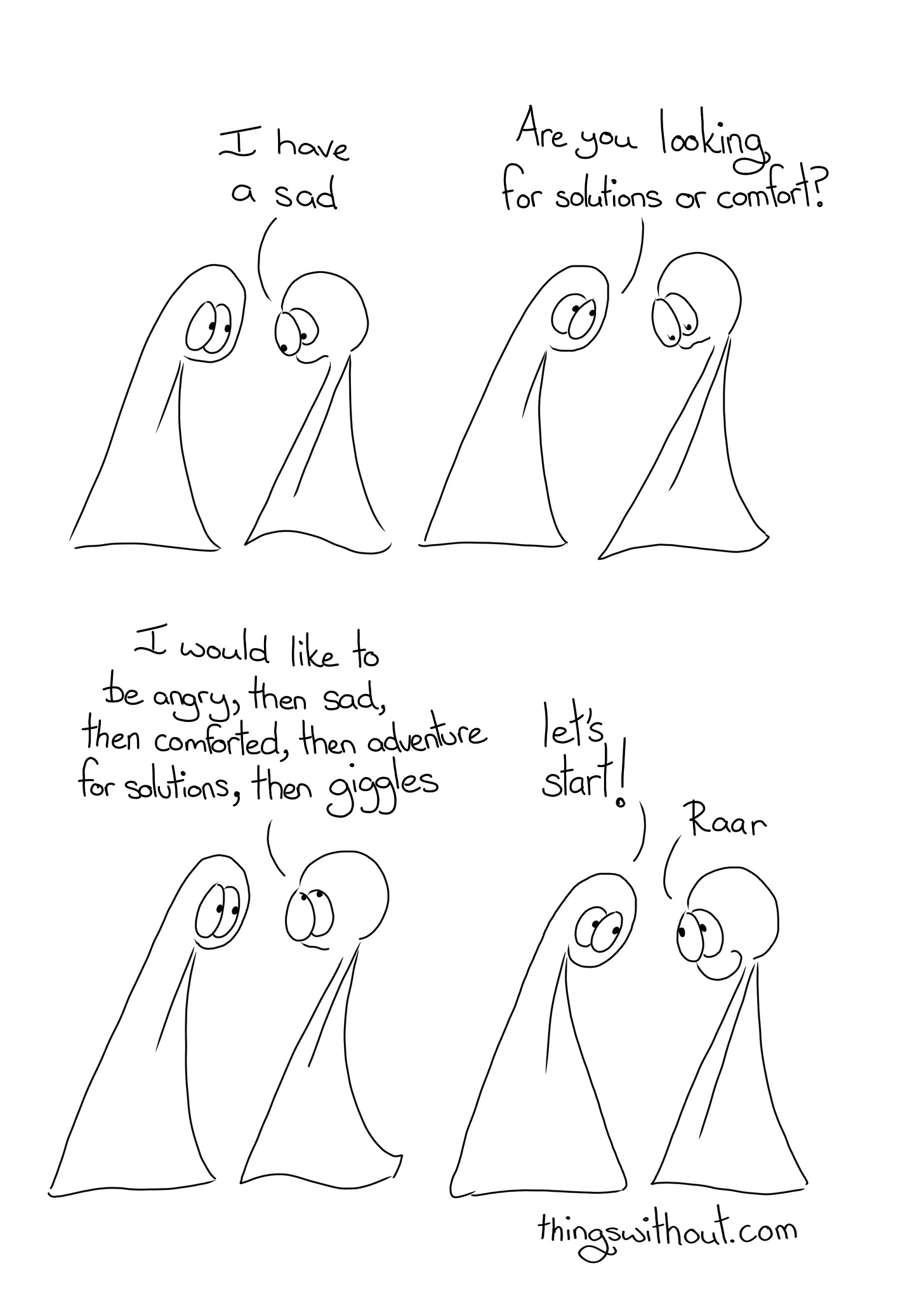

a favorite comic about verbal ventilation and co-regulation, by Liz Argall

Listening

The number one thing I try to do as a healer is to listen. It’s an absolute cornerstone of my training: Ilana Rubenfeld’s book is literally called The Listening Hand. I learned a lot about listening to the body with my hands, but especially since going totally virtual, I’ve learned a lot more about the more usual sort of listening—which I also try to do with my entire body.

Often, as Pete Walker reminds us, much of what a client needs to do is verbally ventilate, or what most of us just call “venting.” Working out your feelings with someone who is listening carefully, commiserating, and attuning to your emotions as you speak can be an incredibly healing process in and of itself. It may sound like a cliche, but a huge part of a therapist’s job is simply this: listening to the client and giving their stories and emotions space to exist without judgment. It’s amazing to me how often clients thank me at the end of sessions where I’ve said barely anything—because it’s so clear that they haven’t had a space to tell their stories.

Co-regulating

When a client seeks therapy, sometimes what’s missing for them is someone to help them identify, feel through, and get a sense of agency around their emotions. Some clients are anxious or agitated frequently enough that it interferes with their functioning. Others dissociate, or bury their emotions as a protection against being overwhelmed. When difficult topics come up, they may find themselves “freaked out,” highly emotional, or out of control, and they don’t have people in their lives who can help them calm their nervous systems down. Shame can come into play, as those big emotions make clients feel they must be burdensome or distasteful to others, sometimes including the therapist.

Co-regulation describes the process by which two (or more) people help each other, both to feel the difficult emotions, and to return to a baseline of safety. A therapist is in a special position to connect with a client effectively even when that client is agitated, and to help them come to a calmer place. This doesn’t mean suppressing emotions; on the contrary, it means helping the client be safe expressing them, and helping them stay in their bodies while they do it.

Allying

This is a big one. Sometimes, when people talk about what therapists are for, they talk about them being “impartial,” meaning that they’re people who are not personally connected to the client, and therefore do not have conflicts of interest. This is why therapists need to be very careful not to see partners, close friends, coworkers, or relatives of clients (unless working in family therapy or couples context).

But the way I think of it is far less impartiality and more total partiality. That is: I strive to be my clients’ staunchest advocate and biggest fan. A therapist, to me, is someone who is always on their client’s side. Part of that role, too, is helping the client identify other people in their lives who are truly on their side, and cultivate that kind of support network.

This doesn’t mean that I approve of every choice clients make, or encourage them to make poor choices just because they think it’s a good idea. I don’t want them to treat others in their lives badly, or treat themselves badly. What it means is that I listen to them, I root for them, I hear them and validate them in their pain, and I help collaborate with them toward solutions that feel good in their bodies. Which brings me to the last big one.

Advising

I listened to a podcast where a couple of therapists spoke strongly against therapists giving advice. I get where they’re coming from, and they’re talking especially about therapists who push for certain solutions with clients without thinking it through. (A particularly egregious example was a therapist who advised an unhappy woman to get a divorce, without first looking deeply into the issues of the client or of the marriage.) Advice of the kind a friend might give off the cuff is not what people ought to go to therapy to get.

However, there is a place for “solutions,” as the cartoon demonstrates, in a therapeutic bond. In particular, there often comes a time after a lot of talk, feelings, exercises, advocacy, and so on when a client might say outright: “What should I do?”

In these moments, it’s very important for the therapist not to give orders, nor even strong suggestions, even though—and I’ll be the first to admit this!—it’s incredibly tempting sometimes to just say “Leave that jerk!” or “Quit that job!” or “Get out of your parents’ house.” If the therapist has spent a lot of time actively listening, helping the client navigate emotions, and being an ally to the client’s healing and growth, then it can be painful to see a client continue to struggle in a failing relationship, abusive household, crushing workload, or other bad situation.

Advising, then, is more a matter of showing the client that they do have choices. Sometimes I’ll turn it back to them: “What do you want to do?” Or, “What would you do if you didn’t have to deal with any of the consequences?” The first question can connect the client to their desire, a critical driver that’s often been taken offline in folks with traumatic backgrounds. The second can help them imagine a way through when thoughts of repercussions are keeping them stuck. A client might say, “If it weren’t for [my kids / the money / the feeling that I owe them], I’d walk out the door tomorrow, no question.” This doesn’t mean the consequences don’t matter. But allowing a client to get in touch with their genuine desire can give them a starting place for action, at which point a therapist can help them make some kind of plan that takes consequences into account, and makes sure the client stays safe.

So, that’s how I think it’s supposed to work. What do you think? The permanent link to these posts does have a comment section, if you’d like to chat about your own experiences with therapy and therapists. Or, contact me directly—this is one of my favorite topics.